If you’ve been following this blog recently, you’ll know that it has been covering my drift back toward film, a process that started a couple of years ago, but really got going in earnest this spring. If you haven’t been following this blog, well, it’s been covering my drift back toward film, a process that really got going in earnest this spring.

To start, I’d like to point you to the catalyst for this post. Ryan Muirhead is a pretty good photographer from Utah, and he has been featured this summer on Framed Network’s show Film. I say he’s pretty good because his images, while appealing both stylistically and aesthetically, don’t drop my jaw like those of other photographers whose work I’ve been spending time with lately, such as Steve McCurry or Mary Ellen Mark (whose Prom exhibit is currently at the Philadelphia Art Museum; go see it). The comparisons are probably not a good idea…each is a very different kind of photographer, but it’s who I’m looking at these days. What I like about Ryan is his ability to talk about process. He talks about liking to shoot film because he enjoys the process of it. But he also talks about, and has clearly spent a good deal of time thinking about, the artistic process and what it means to pick up a camera and create.

In general, Film has been fun to watch, but it is not a show about shooting film. Rather, it is a show about photographers who shoot film, and the lifestyle-style direction of the show leaves out technical talk while showing that shooting film is an entirely rational decision that can result in exquisite, edgy, modern work.

Then along comes Episode 14 (free registration required). At about the 23:45 mark, Ryan starts talking about photography. It’s an episode about continuous lighting, but that’s not what he’s talking about. He’s talking about photography. Or as he puts it, “truth, beauty, life, and fear”, a phrase that brings to mind an introspective passage from “West-Running Brook,” one of my favorite poems (it’s by Robert Frost): “And it is time, strength, tone, light, life and love, and even substance lapsing unsubstantial, the universal cataract of death that spends to nothingness, and unresisted, save by some strange resistance in itself, not just a swerving, but a throwing back, as if regret were in it, and were sacred.” Ryan puts it many other ways as well, but that’s the one that snapped me to attention, made me listen more closely, then listen again, and then write down everything he said. The jangly, anonymous acoustipop fades away, the rapid-fire editing takes a break, the tomfoolery and roughhousery are put aside, all sound is cut out except for Ryan’s voice, which sounds like a very intelligent rock slide. For nine uninterrupted, gut-wrenching minutes he goes on, pouring forth a tremendous flood from the soul that is arresting, liberating, intoxicating, sobering, grounding, motivating, heartbreaking, tragic, and triumphant. It’s about photography; it’s about coping with survival and coping with terror; it’s about how to live.

So why do I pick up a camera and create? My answer is not nearly as compelling as his, but it, too, originates from a driving need to make sense of things. People I know are always suggesting beautiful things I could photograph, and I get the sense that they feel a little hurt when I don’t always show interest. I hold with Albert Camus, and to a lesser extent with deconstructionists, that the physical world, no matter how awe-inspiring, is devoid of meaning, and that all that we find meaningful is a product of our minds, of what we believe. In my life before photography, I was an English teacher, and one idea that I was interested in, and that informed how I taught writing, was the idea of “meaning-making”. It is the process by which a constructive process encourages the thought and reflection necessary to gain knowledge and understanding of both the world and the self. Very mundane things, if properly investigated, can lead to great insight, but we each have to create that insight for ourselves. Even something as grand as spirituality and religious illumination means little if not supported by individual experience and reflection. If we wish to have some amount of control over what we find meaningful, if we want to look out onto the world and inward onto our selves and have a sense that they are at least partially understood, if we look to have a say in the structures of significance that we build our lives around, then we must each engage in some meaning-making activity.

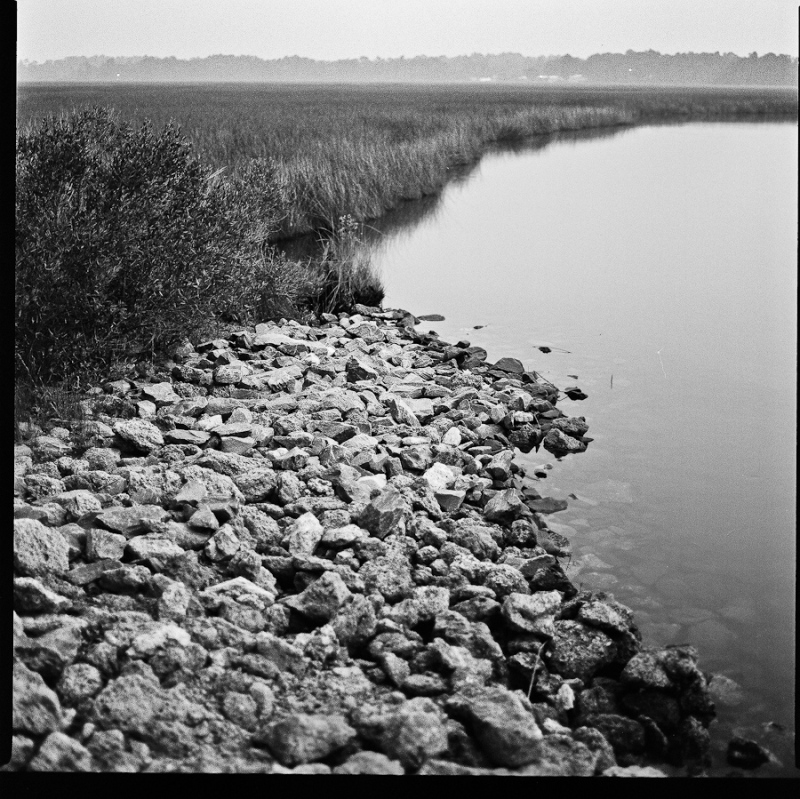

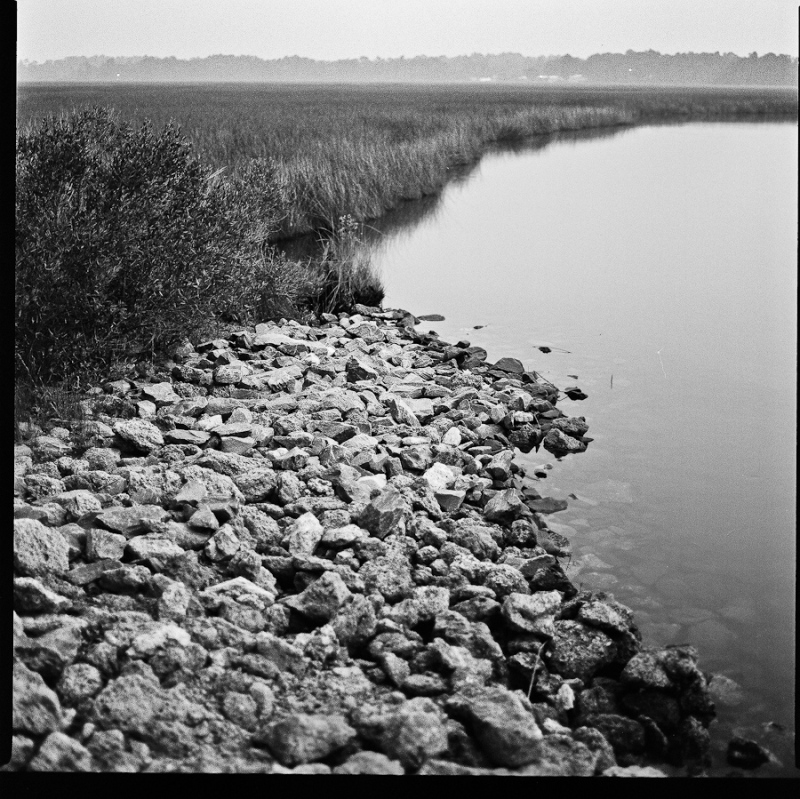

Photography (and writing, too, still) is this activity for me. I don’t approach photography in a way that demands that every image be perfect (there is no perfect image, anyway); I approach photography in a way that asks each image to build on the ones before it, and the concrete shot limits on a roll of film help me structure that process. A roll of film is a thought process, an investigation. It has a theme, a location in time and space. It is about something that other rolls are not about. It is a journal entry. The simple act of taking an image confers importance onto a subject, and the repeated shooting of the same thing, whatever that thing may be, or however loosely defined, in different ways confers the subtleties and inferences that make knowledge, and self-knowledge, interesting.

But because the physical world can’t hold meaning itself, the action of meaning-making builds the meaning in our minds. The way we shoot portraits reflects the way we interact with people. The way we shoot the land reflects the way we interact with our environment. The way we shoot an event reflects how we discern time and action. The way we shoot a still life reflects our capacity to gaze. And reflecting on the resulting images will show you something about yourself, which is itself an act of meaning-making.

In this way, photography becomes a method of grounding, or centering, of meditation. It becomes not a tool of image-making, but of self-construction and maintenance. I look through the viewfinder, on onto the ground glass, and I ask myself, “Why is this important?” And the answer to that is the beginning of discovering or rediscovering, making or repairing meaning. I like film because it leaves behind a physical artifact of this process.

And it is a compelling process.